HOW I BECAME A CRUSADER AGAINST WESTERN MEDIA’S RACIST DEMONIZATION OF AFRICA

- Milton Allimadi

- Jul 20, 2023

- 16 min read

Updated: Jul 27, 2023

By Milton Allimadi

It came as a great surprise to me when I found out from my first grade teacher that I played with lions and elephants in Africa.

This was back in the 1960s, when I was a kid attending school in Washington, D.C. One day, shortly after the semester began, the teacher made me stand in front of my impressionable peers, other five and six year olds. I don’t recall that I’d done anything wrong to be singled out before the class but my first assumption was that I was in some sort of trouble.

"Milton's father is an important chief in Africa and he gets to play with lions and elephants," the teacher, a white lady, announced.

I was amazed. Then, I noticed some of my peers gasping delightfully. I remember looking up at her, puzzled.

"Isn't that right Milton?" she added, firmly squeezing my shoulders.

“‘Milton's father is an important chief in Africa and he gets to play with lions and elephants,’ the teacher, a white lady, announced.”

"Yes," I said, nodding and acquiescing to the lie.

My family had moved to the U.S. a few months earlier, arriving from Uganda, having traveled from my hometown of Gulu and then via Kampala, the capital. Obviously at the time I was too young to know why we were coming to the United States of America.

My now late father, E. Otema Allimadi, had been appointed as Uganda's ambassador to Washington and to the United Nations, and High Commissioner to Canada. He'd been appointed by President Milton Obote, alongside whom he'd struggled for Uganda's independence from the United Kingdom, which was won in 1962.

The late Otema Allimadi seated on the panel at the United Nations

My popularity shot up after my teacher's concoction. I'd be dropped off at school in the Ugandan embassy’s official Mercedes. But the other kids wanted to hear me regale them with tales about my jungle adventures with my animal friends. So I indulged them with fake stories. I imagine I must have drawn my material from whatever depictions of African “jungles” that I watched on the same American cartoons that they also saw. My teacher had turned me, unwittingly, into a propagator of racist stereotypes about Africa.

I never told my parents about this episode, which became one of the transformative incidents in my life, shaping me into a crusader against racist demonization of Africa in Western media.

My family returned to Uganda in 1971 when Idi Amin overthrew Obote. Now out of government, my father had retired into commercial farming near our home town of Gulu, about 200 miles from Kampala. We had a home in the town but often lived in another house in our village of Bungatira. One day, our father who used to head to Gulu town each morning, never returned that evening. I was nine years old at the time; Andrew was eight; Walter seven; Sue was five, Doris was three, and Barbara was an infant who’d just been born in Uganda.

“My teacher had turned me, unwittingly, into a propagator of racist stereotypes about Africa.”

At the time, I did not know that Amin was trying to kill my father.

My mother, Alice Lamunu, told me and the ones who were old enough that our father was “in a safe place” and would soon be back home. But even at that young age, I wondered. I’d often heard my parents and other grown ups in whispered conversations after some prominent family friend went missing.

One day, the following year my mother told me and my siblings to get ready. We were visiting her relatives in a village called Katikati. One of her youngest brothers, Oloya, was one of my favorite uncles so I was thrilled. We packed very light because the visits never lasted more than a few days. But when we boarded the bus in Gulu town, we traveled for several hours and instead ended up in Kampala, the capital. We spent a few days in Kampala at the home of one of my father’s friends. Even though he now worked for Amin’s intelligence services he remained friendly to our father. One night my mother took me aside, as the eldest of her children, and told me we were on our way to join our father in Tanzania. It was only then that I learned where our father was and that we were escaping Uganda to join him. But first we’d have to cross into Kenya, using the fake document that my father’s friend had prepared for my mother.

It was a dangerous time. Amin’s regime officials had murdered many of my father’s colleagues from Obote's former government. We needed to flee while we could.

“At the time, I did not know that Amin was trying to kill my father.”

I remember some policemen and soldiers going through my mother’s papers at the border. I think I had watched too much television while living in the States. I kept my eyes on the holstered pistol of one of the policemen. I’d made up my mind that if they discovered we were trying to escape and tried to arrest us, I’d grab his pistol and hold him hostage until they let my family cross into Kenya. Luckily, it never came to that and we were allowed to leave Uganda.

It was much later, while in Tanzania that I learned how my father had escaped Idi Amin. One day, a jeep full of soldiers trailed him in his blue Mercedes from Bungatira to Gulu town. Everywhere he went they followed and parked close by. That was the sign that your time was up. My father drove to the local police station and asked to record a statement to report the soldiers. The commander of the soldiers stormed in and warned the police not to take a statement and they complied. My father’s routine was to sit with friends, chatting all afternoon at the outside bar in Acholi Inn, the best hotel in Gulu, then drive back home at sunset. He realized the plan was for the soldiers to follow him along the unpaved and unlit road between Gulu and Bungatira at dusk and then whisk him away for execution.

“That was the sign that your time was up.”

He sat with his friends. He could see the jeep parked behind his car. One time, he went to the bathroom, he climbed out the window, and he disappeared. The soldiers waited and waited. When they realized that the owner of the Benz was not coming back, my father had been well on his way into exile with the assistance of friends and some disguises. He never divulged any more details beyond this.

To say my family's living standard in exile was "modest" would be an understatement. My now late mother always made sure we never starved. As only mothers can do, she haggled and bargained with vendors in the markets so that every shilling fetched beyond its actual value and she was able to walk away with hefty amounts of beans, rice and vegetables. We got our clothes, hand-me-downs, from a refugee relief center. The days of living the high life of an ambassador’s family were long gone. Tanzania taught us humility and humanity.

I developed my great love for reading in Tanzania. Books, newspapers and magazines allowed me to travel to different countries and times in history. Even though we barely had enough for food, my father never turned me down when I asked for money to buy a book. Reading was my antidote to the poverty the family endured. Yet as early as age 12, I was already able to notice that Africans were depicted as inferior to Europeans and people of European descent in the magazines and newspapers I read at the United States Information Services (USIS) center and the British Council Library. Africans were "tribal" people or "tribesmen." These terms were always used to suggest that Africans were inferior to white people. This always brought back memories of my first grade teacher. The tribalization of Africa was evident even in the popular "Tin Tin" comics.

In 1978, in a desperate attempt to divert the attention of his own people from Uganda's economic collapse Gen. Amin invaded Tanzania. Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere ordered a counter-attack and in April 1979, Amin was driven from power and into exile. My family returned to Uganda and my father resumed his political career, first as foreign minister in a transitional government, and later as prime minister, when Obote became president again. Obote was overthrown for a second time in 1985.

“Africans were ‘tribal’ people or ‘tribesmen.’ These terms were always used to suggest that Africans were inferior to white people.”

Meanwhile, I came back to the U.S. in 1980 to attend Syracuse University. I’d been away too long and forgotten the necessary precautions. I arrived on a bitter winter day in a Spring semester. I had to spend a couple of days at an airport hotel because the snow-covered roads to the city were impenetrable. Yes, I had on a wool suit but I had no winter coat. I had on leather soled shoes with no traction. When I did make it to campus, my cab dropped me at the wrong location, not the registrars. I slipped on the snow and fell countless times as I lugged my suitcase to the registrar’s office and then later to my dormitory. Welcome to America.

I was in a Freshman English class one day when the professor, a white man, read from Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness." I don't remember the exact passages but I imagine it was the part where Conrad’s narrator, sailing on the River Congo, observes:

“We were wanderers on prehistoric earth, on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet. We could have fancied ourselves the first of men taking possession of an accursed inheritance, to be subdued at the cost of profound anguish and of excessive toil. But suddenly, as we struggled round a bend there would be a glimpse of rush walls, of peaked grassroofs, a burst of yells, a whirl of black limbs, a mass of hands clapping, of feet stamping, of eyes rolling, under the droop of heavy and motionless foliage. The steamer toiled along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy. The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us – who could tell? We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse.”

“Welcome to America.”

This is also one of the passages that renowned Nigerian author, the late Chinua Achebe, criticized when he demolished Conrad in his essay “An Image of Africa: Racism In Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness.’”

But during my English class I could only cringe and feel like burying my head in the sand as the professor – with a gleeful tone – read racist depictions of Africans from the book, again and again.

He claimed it was the "best book" ever written in the English language. My classmates, mostly white students, may have taken his words to heart. The most devastating part of that episode to me – as was the case with my first grade teacher many years earlier – was that I wasn't intellectually equipped to challenge this teacher. It was as if this teacher had also, in his own way, pulled me in front of the class again to display me as an example of “jungle Africa.” So Conrad's image of Africa carried the day. How could it not have? I didn’t utter a single word of objection.

I completed an undergrad and Master’s degree in economics at Syracuse. I'd actually wanted to study film. But my father, may he rest in peace with our beloved ancestors, said that wasn't a real profession; he paid, so he had veto power.

“It was as if this teacher had also, in his own way, pulled me in front of the class again to display me as an example of ‘jungle Africa.’”

I was hired for a research position with the City of New York, but I found myself spending many hours writing to editors of various newspapers, including the Syracuse Post Standard and later the New York Times, complaining about the depiction of Africans or Haitians. When it came to Africa, the constant reference to “tribes,” and “tribal,” or “tribesmen,” evoked the “jungle” image; it gave the impression of a continent of irrational human beings and offered no context or meaning to the many challenges they faced. In the case of Haiti, the stories often neglected how the imperialist interventions by the U.S. had contributed to the country’s woes, including past military occupation and support for the Duvalier dictatorship.

“I found myself spending many hours writing to editors of various newspapers, including the Syracuse Post Standard and later the New York Times, complaining about the depiction of Africans or Haitians.”

Rather than shout from outside the gates I decided to become a reporter. I applied to the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia and was accepted for the graduating class of 1992.

My Master’s paper documented the evolution of racist depictions of Africa in the United States, with a focus on the New York Times, whose writings about the continent dates to at least the 1870s. I focused on the Times' coverage of the fight for Africa's independence from the 1950s, through the struggle against apartheid in South Africa in the 1980s. What set my Master’s paper apart were the exclusive correspondences I unearthed, between New York Times reporters sent to Africa beginning in the 1950s, and their editors here in New York. Many of the letters captured the intensity of their virulent racism toward Africa.

I had no idea what I would discover in the Times’ archives. Some of the letters were so racist that even though the archivist told me I was permitted to make as many copies of the documents I needed for my research, I found it hard to believe him. So I slipped some copies into my shirt just in case he changed his mind and said I couldn’t walk out with them. But he was true to his word and allowed me access to the files of any one of the reporters or editors that I asked for. I went there almost every day for several weeks. I was developing a better understanding of the mindset that determined the Times’ early African reporting and its influence on contemporary coverage. I did not want anything to jeopardize my access to the archives so I kept my research findings to myself and shared it with only two professors: my Master’s advisor, whom I wasn’t close to, and Prof. Sam Freedman, one of the most respected teachers at the Journalism School and himself a former Times reporter.

Even by the standards of the 1950s, the racist animus toward Africans by some Times reporters like Homer Bigart, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and the foreign news editor Emanuel Freedman chilled me, especially since the Times presents itself as a citadel of liberal enlightenment.

“Rather than shout from outside the gates I decided to become a reporter.”

The personal racism toward Africans by the reporter and editor was reflected in what were published purporting to be "news" articles in the Times. In an undated letter from Accra Ghana, in late 1959, Bigart wrote:

"I'm afraid I cannot work up any enthusiasm for the emerging republics...The politicians are either crooks or mystics. Dr. Nkrumah is a Henry Wallace in burnt cork. I vastly prefer the primitive bush people. After all, cannibalism may be the logical antidote to this population explosion everyone talks about."

Bigart liked using terms such as "cannibalism," "tribal," "macabre" and "grotesque" in his articles about Africa.

Bigart even made up stuff so his articles could depict Africans in the most "savage" or "primitive" light.

In a letter dated May 29, 1960 to Freedman, he complained about not being able to find pygmies to interview them about the meaning of independence of Congo from Belgium. Yet, when his article appeared in the Times on June 5, 1960 under the insulting headline "Magic of Freedom Enchants Congolese," Bigart wrote:

"Independence is an abstraction not easily grasped by Congolese and they are seeking concrete interpretations...To the forest pygmy independence means a little more salt, a little more beer."

Courtesy of The New York Times

Never mind that an estimated 10 million Congolese had been exterminated under the regime of Belgian King Leopold II.

All the Congolese wanted was more salt and beer.

“Bigart even made up stuff so his articles could depict Africans in the most ‘savage’ or ‘primitive’ light.”

Freedman was delighted by Bigart's racist depictions of Africa and encouraged it.

"By now you must be American journalism's leading expert on sorcery, witchcraft, cannibalism and all the other exotic phenomena indigenous to darkest Africa," he wrote to Bigart, in a letter dated March 4, 1960. "All this and nationalism too. Where else but in the New York Times can you get all this for a nickel?"

When stories by its other reporters sent to Africa did not sufficiently demonize Africans, some Times' editors took matters into their own hands and engaged in what today would be called "fake news."

My research unearthed a letter dated June 5, 1967 by a Times foreign correspondent named Lloyd Garrison – who'd covered the Nigerian-Biafran war – complaining about the insertion of a sentence describing "small pagan tribes dressed in leaves," into his article. Garrison had not seen the alleged pagan tribe in Nigeria and had not written about it. Times' editors just made it up and

inserted it into his article.

Given the exchanges between Bigart and foreign news editor Freedman, I wasn’t shocked to find out that the Times had produced such a malicious concoction. I still found it upsetting that editors at such a major publication could treat Africans in such a contemptuous manner while pretending to be “objective” journalists. I concluded that the best thing for me to do was focus on exposing this ugly part of The New York Times’ history and its own contribution toward disseminating the global racist perception of Africa.

Courtesy of Global Citizens

“When stories by its other reporters sent to Africa did not sufficiently demonize Africans, some Times' editors took matters into their own hands and engaged in what today would be called ‘fake news.’”

My Master’s paper won the prestigious James A. Wechsler Award at the journalism school at the end of the semester. This time it felt different when I was called in front of my peers for something connected with Africa. Columbia Journalism Review invited me to submit the paper for publication. But it turns out they bit more than they could chew. Out of fear of how the Times might react, they reneged on publishing. I was able to get a copy of their own edited version of my paper which to me left no doubt they were afraid of the Times. This is what The Review’s editors had written on my behalf, without my permission: “Recently, the Times granted me access to its archives, including correspondences from the 1950s, when the paper sent Bigart to Africa on a temporary assignment. After studying the archival material, I interviewed several present and former Times reporters. The following excerpts from that material and from lengthy interviews are not intended as an indictment of the Times – whose African coverage has occasionally been distinguished – but as a means of highlighting a problem that all news organizations need to address.”

I was disgusted by the CJR’s cowardice. I wrote a letter to the Times’ publisher Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr., and said since the CJR was obviously afraid of the Times, I wanted to make sure he read my paper and I sent him my unedited version. Joseph Lelyveld, who was then the Times managing editor, wrote to me and acknowledged that I had uncovered “crude and ugly” language in my research.

In the many years after graduating from Columbia, I took my journalism first to the Times as a stringer and later to The City Sun, a Black-owned weekly newspaper, as an investigative reporter and editor. When the City Sun went out of business, I launched Black Star News in 1997 with seed money from Camille Cosby.

I remember I had run into Bill Cosby – this is many years before his legal problems related to rape allegations and charges – after we’d both finished jogging in the East River Park before his Rolls Royce pulled up to whisk him away. Later, I’d sent him a copy of Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart,” one of my favorite books and he’d sent me a “Thank You” note. So when I drew up a business plan for my publication and sent it to famous wealthy people, I made sure that the package to Cosby included a reminder about the jogging encounter and the Achebe book. Some months later I received one of those envelopes with a window – that normally means a bill so I didn’t open it for a couple of days. When I finally did, it was a check from Camille Cosby. I soon launched Black Star News as a monthly publication with the help of my girlfriend at the time Mana Lumumba-Kasongo and a Ugandan friend named Ben Otunu. I sent a copy of the paper to the Cosbys each month. Camille sent me two more checks.

Undaunted by the CJR’s attempt to censor my revelation about the Times’ ugly past with respect to Africa, I decided to work on a book, broadening my research on the historic racist depictions of Africa in Western writings. My critique now included Newsweek, Time magazine, National Geographic magazine and the books by the European so-called "explorers" who traveled to Africa and "discovered" lakes, rivers and mountains even though they were led there by African guides. They replaced African names with European ones.

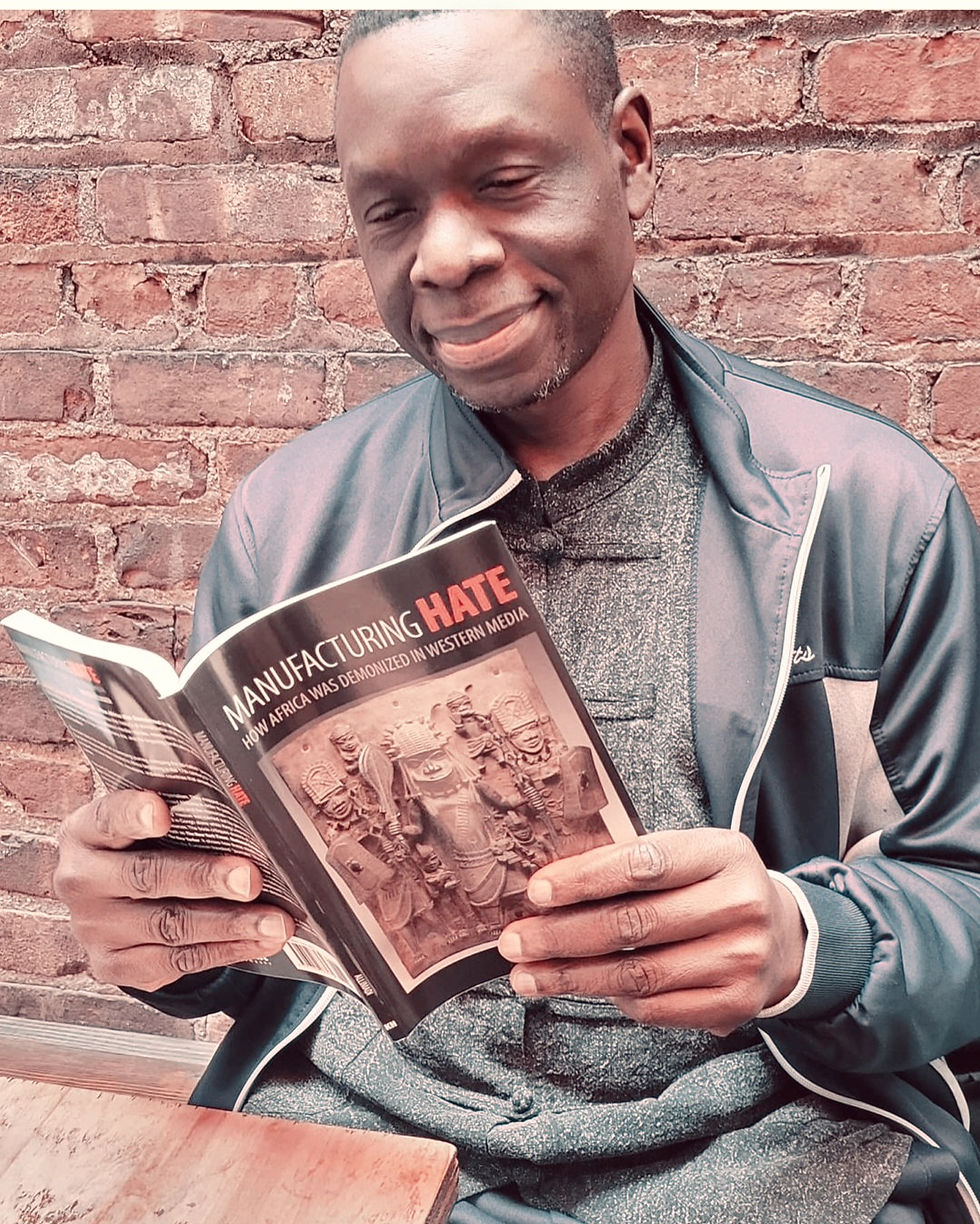

My work culminated in the publication of my book "Manufacturing Hate: How Africa Was Demonized In Western Media." (Kendall Hunt Publishing Co., 2021).

So far, there have been only two reviews of the book – both were good – and one writeup, in Journal-ism. For example, the one in Review of African Political Economy by Prof. Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, a prominent Congolese professor of African-American, African and global studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, holds up my book as an instrument that debunks the Western myth that Europeans brought civilization to Africa when in fact many African civilizations existed before European states were founded. “Overall, this is an outstanding work of scholarship, and that should be read by undergraduates and students enrolled in studies of journalism and communications generally, as well as by the general public,” Prof. Nzongola-Ntalaja writes.

“My work culminated in the publication of my book ‘Manufacturing Hate: How Africa Was Demonized In Western Media.’”

KIRKUS review said my book was, “A study of how Western reporters and editors have contributed to a distorted and derogatory representation of African people…A revelatory survey of problematic coverage of Africa throughout history.”

The Times, not surprisingly, did not review the book. Ironically, on December 22, 2020 the New York Times wrote a long article about the Kansas City Star’s apology for its past demonization of Black Kansans. When my book was published, in addition to sending a copy to the Books Editor at the New York Times, in May 2022, I sent a copy to the current Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger. I reminded Sulzberger that the Times had written about the Kansas City Star’s apology and that it would be appropriate for the Times to also apologize for its own demonization of Africans. I received no response.

“...a study of how Western reporters and editors have contributed to a distorted and derogatory representation of African people…”

I, personally, believe many of the so-called "liberal" corporate media are reluctant to review a book that exposes a very ugly chapter in the Times' African coverage. The CJR revealed this fear to me decades ago. However, I operate by the Bob Marley mantra, “When one door is closed, many more are open.”

I consider "Manufacturing Hate..." as my most important achievement in journalism to this day. Any African who has been frustrated by the racist depictions of Africa and its people – which continues in our contemporary era – can now use the information from my book to counter the demonization.

So, I give thanks to both my first grade teacher who claimed that I played with elephants and lions, and to my Freshman English professor who so loved Conrad, for setting me on this crusade to restore the dignity of Africa.

Milton Allimadi is a journalist and writer based in New York City. He publishes BlackStarNews and hosts a weekly radio show on WBAI 99.5 FM New York Radio. He is also an Adjunct Professor in the Africana Studies Department at John Jay and at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia. He is still searching for a publisher for "Manufacturing Hate..." for the Africa market. https://tinyurl.com/4t7th4ce He is also the author of “Adwa: Empress Taytu & Emperor Menelik in Love & War” available via Amazon https://tinyurl.com/2rd6dbfm He can be reached for public speaking engagements via mallimadi@gmail.com.

Twitter @allimadi

Looking forward to reading the book. The article alone is already a hefty tool to defend against the gaslighting of a continent. Thank you. GCS